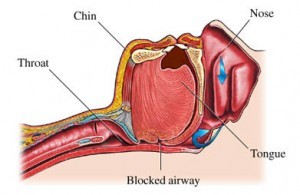

An ancillary study to the Look AHEAD trial found that intensive lifestyle interventions designed to promote weight loss in obese individuals with Type 2 diabetes also helped reduce obstructive sleep apnea in the same patients.

An ancillary study to the Look AHEAD trial found that intensive lifestyle interventions designed to promote weight loss in obese individuals with Type 2 diabetes also helped reduce obstructive sleep apnea in the same patients.

Over the course of the four year study, patients who underwent intensive interventions demonstrated an approximately four point reduction in apnea-hypopnea index. Meanwhile, the control group saw a four-point increase in the same metric, according to Gary Foster Ph.D., with Temple University in Philadelphia. Dr. Foster reported the findings of the study at a meeting of the Obesity Society.

Patients with the more severe obstructive sleep apnea at the beginning of the study also saw the greatest benefit and reported the largest gains. However, Dr. Foster commented that intensive interventions would not be a replacement for other sleep apnea therapy: the patients in the study had a mean apnea-hypopnea index of 20, which means that a four-point reduction would not be enough to eliminate symptoms without the help of other treatments.

“I don’t want to give you the impression that this is an alternative treatment to [continuous positive airway pressure treatment],” said Dr. Foster. “It’s probably a complementary treatment.”

The study, called Sleep AHEAD, was an ancillary of the Look AHEAD trial, which studies the benefits and effectiveness of intensive lifestyle interventions for obese individuals with Type 2 diabetes. The interventions are designed to promote weight loss in those individuals through education and diabetes support.

The Sleep AHEAD study aimed to determine whether the patients’ weight loss would also reduce the severity of sleep-related breathing disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea. It had been previously demonstrated in smaller studies that weight loss did have a positive effect on sleep apnea.

The study participants were given a questionnaire which aided researchers in identifying the severity of each individual’s sleep apnea. Patients who were already receiving treatment for sleep apnea or who had received surgery to treat the condition were not included in the pool of participants; researchers wanted to study patients who were not receiving current treatment for sleep apnea.

In all, 305 patients participated in the study, undergoing polysomnograms at their homes to measure symptoms of sleep apnea. Researchers rated participants on the severity of sleep apnea. Those with an apnea-hypopnea index of 5 or less were classified as free of sleep apnea; a score of 5 to 15 was diagnosed as mild; a score of 15 to 30 was moderate, and a score of 30 or more was severe.

Mean score among the participants was 20.5, with 13.4 percent of patients classified as not having sleep apnea. Participants with mild sleep apnea made up 33.5 percent of the study group while moderate patients made up 30.5 percent and severe patients made up 22.6 percent.

A year into the intensive intervention, patients had lost an average of 24 pounds while patients in a control group did not demonstrate any weight loss. Additionally, patients undergoing lifestyle interventions saw a reduction in apnea-hypopnea index of about six points while control patients had an increase of four points.

Four years into the study, intervention patients were more likely to have seen an improvement in their sleep apnea severity classifications (40 percent versus 15 percent) and were also more likely to experience a remission of symptoms (20 percent versus 3 percent).

Though weight loss seemed to be associated with reduction in sleep apnea, Dr. Foster commented that a healthier lifestyle in general could be more responsible for the positive changes.

“The likely hero, I think, is fitness,” said Dr. Foster, citing that previous research has shown that increased fitness levels even in the absence of weight loss can lead to improved sleep apnea.

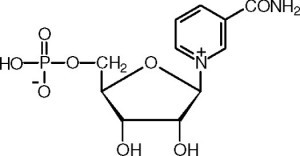

New research has demonstrated that a type of sugar extracted from buckwheat, called D-fagomine, could help diabetics keep their blood glucose levels well-managed and may offer prebiotic activity in small doses.

New research has demonstrated that a type of sugar extracted from buckwheat, called D-fagomine, could help diabetics keep their blood glucose levels well-managed and may offer prebiotic activity in small doses. A team of scientists reported on October 5 that they had successfully utilized cloning technology to create

A team of scientists reported on October 5 that they had successfully utilized cloning technology to create  A team of United States-based scientists are hopeful that new research on a natural chemical found in body cells could set the stage for the development of a vitamin-like pill that could prevent diabetes or perhaps even reverse the disease completely.

A team of United States-based scientists are hopeful that new research on a natural chemical found in body cells could set the stage for the development of a vitamin-like pill that could prevent diabetes or perhaps even reverse the disease completely. A study published in the October issue of the journal “Diabetes Care” has demonstrated that, in patients with Type 1 diabetes who receive intensive

A study published in the October issue of the journal “Diabetes Care” has demonstrated that, in patients with Type 1 diabetes who receive intensive  A recent randomized trial showed that increasing the intensity of weight loss interventions only in patients who do not succeed in reaching their goals may be an effective alternative to typical approaches.

A recent randomized trial showed that increasing the intensity of weight loss interventions only in patients who do not succeed in reaching their goals may be an effective alternative to typical approaches. A new study warns that eating food too quickly more than doubles an individual’s chance of developing impaired glucose tolerance, also known as

A new study warns that eating food too quickly more than doubles an individual’s chance of developing impaired glucose tolerance, also known as  A study recently published in the journal “Cancer” has discovered that therapy with the drug tamoxifen — an oral

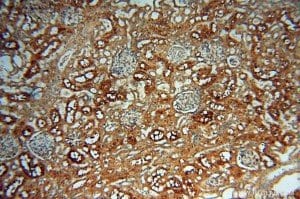

A study recently published in the journal “Cancer” has discovered that therapy with the drug tamoxifen — an oral  Doctors and scientists have long known that people with Type 2 diabetes are at an increased risk of developing certain types of cancer. Until recently, the mechanisms behind the link between the two diseases have been unclear to medical professionals.

Doctors and scientists have long known that people with Type 2 diabetes are at an increased risk of developing certain types of cancer. Until recently, the mechanisms behind the link between the two diseases have been unclear to medical professionals. A large meta-analysis of

A large meta-analysis of