Researchers from the Stanford University School of Medicine have discovered that the artificial activation of an important molecular pathway could someday be used to treat various diseases. The pathway is responsible for decreases in the growth of cells that produce insulin, and is activated naturally as an individual grows older. The findings were published in the October 12 edition of the journal “Nature.”

Researchers from the Stanford University School of Medicine have discovered that the artificial activation of an important molecular pathway could someday be used to treat various diseases. The pathway is responsible for decreases in the growth of cells that produce insulin, and is activated naturally as an individual grows older. The findings were published in the October 12 edition of the journal “Nature.”

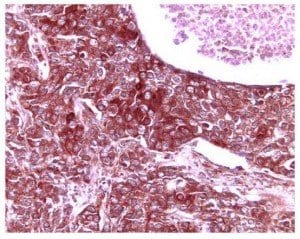

The pathway being studied appears in both mice and humans. It is activated by the expression of a particular molecule called platelet-derived growth factor receptor, or PDGF-receptor for short. Expression of this molecule naturally decreases over time, as does the growth of beta cells in the pancreas, which release insulin that helps removes glucose from the bloodstream and transports it to cells where it can be used as energy.

Scientists have long known that the growth of pancreatic beta cells decreases dramatically over time. In young and newborn humans and animals, beta cell proliferation is abundant.

Another molecule known as Ezh2 appears to be involved in the pathway that reduces production of beta cells, as expression of the molecule decreases over time. Scientists were unaware, however, what caused the change in expression of Ezh2.

Researchers on the study discovered that, in juvenile mice, the expression of PDGF receptors was reduced in the islet cells of the pancreas in a similar pattern to that of the decreases in beta cell production.

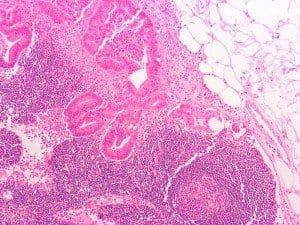

Blocking the expression of PDGF receptors in young lab mice—two to three weeks old—caused decreases in Ezh2 production and the number of pancreatic beta cells than control animals whose PDGF receptors were not affected. The mice with reduced Ezh2 production also demonstrated slightly higher blood sugar levels than control subjects and could not remove glucose from the blood stream as effectively when they were given a high glycemic load, such as after a meal heavy in carbohydrates.

A lack of expression in PDGF receptors also affected fully-grown lab mice: their ability to replace beta cells was diminished when the cells were destroyed by a compound that the researchers administered to the animals. They also developed severe diabetes after their beta cells were destroyed.

“We’re hopeful that soon we might be able to manipulate this pathway in a therapeutic way in humans,” said Seung Kim, M.D., Ph.D., senior author of the study and a professor of developmental biology at Stanford University. Kim believes that scientists may one day develop a therapy that activates the pathway to promote the regrowth of beta cells or prevent their destruction.

“Perhaps by rekindling its expression and then activating it through a drug we could give in an injection or through some other route. This could be a kind of one-two punch against diabetes,” continued Kim.

If scientists can develop a therapy that promotes growth of beta cells, it could offer a new method of treating or preventing diabetes that differs from current therapeutics, which mostly focus on maintaining healthy blood glucose levels. Replacing pancreatic beta cells could allow the body to produce its own insulin to regulate blood glucose instead of relying on insulin injections or other medication to control blood sugar.

“This gives us a handhold onto a vaster problem: how to control human beta cell proliferation in a therapeutic way,”

Additionally, the researchers commented that they found other molecular patheways related to the loss of beta cells due to aging that have not yet been explored.

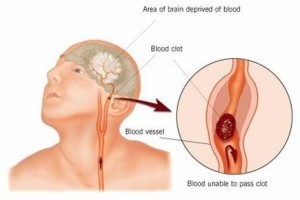

A recent population-based study conducted by researchers at Columbia University in New York found that patients who had been diagnosed with diabetes for a period of ten years or more were over three times more likely to suffer ischemic stroke. The study, called the Northern Manhattan Study, was a large, longitudinal investigation that allowed researchers to study how risk changed over long periods of time.

A recent population-based study conducted by researchers at Columbia University in New York found that patients who had been diagnosed with diabetes for a period of ten years or more were over three times more likely to suffer ischemic stroke. The study, called the Northern Manhattan Study, was a large, longitudinal investigation that allowed researchers to study how risk changed over long periods of time. For individuals with Type 1 diabetes, maintaining healthy blood sugar levels could be not only a necessity for long-term health, but also the key to staying mentally sharp. A study published in the online version of the journal “Diabetes” states that increased exposure to hyperglycemia — elevated levels of blood sugar — is associated with negative effects on brain size, including a decrease in whole brain gray matter. Meanwhile, hypoglycemia is associated with more severe decreases in occipital/parietal white matter volume.

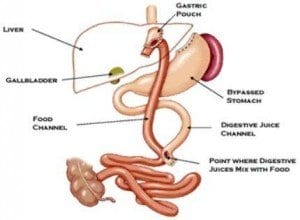

For individuals with Type 1 diabetes, maintaining healthy blood sugar levels could be not only a necessity for long-term health, but also the key to staying mentally sharp. A study published in the online version of the journal “Diabetes” states that increased exposure to hyperglycemia — elevated levels of blood sugar — is associated with negative effects on brain size, including a decrease in whole brain gray matter. Meanwhile, hypoglycemia is associated with more severe decreases in occipital/parietal white matter volume. The Utah Obesity Study has provided the first prospective, long-term controlled trial on the effects of gastric bypass surgery. The trial discovered that the cardiometabolic improvements associated with recent gastric bypass surgery also persist over long periods of time.

The Utah Obesity Study has provided the first prospective, long-term controlled trial on the effects of gastric bypass surgery. The trial discovered that the cardiometabolic improvements associated with recent gastric bypass surgery also persist over long periods of time. A study conducted by researchers at Kaiser Permanente shows that those with Type 2 diabetes would be wise to work at improving their cholesterol. According to the findings of the study, raising HDL cholesterol — or “good” cholesterol — could be associated with a reduction in the risk of stroke and

A study conducted by researchers at Kaiser Permanente shows that those with Type 2 diabetes would be wise to work at improving their cholesterol. According to the findings of the study, raising HDL cholesterol — or “good” cholesterol — could be associated with a reduction in the risk of stroke and  According to researchers at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom, a rare and serious form of hypoglycemia can be traced back to a hereditary disposition.

According to researchers at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom, a rare and serious form of hypoglycemia can be traced back to a hereditary disposition. Juvisync, a pill that combines

Juvisync, a pill that combines  A study conducted at the University of Wisconsin-Madison has identified a gene that could increase susceptibility to diabetes in those who carry it. Researchers discovered the gene in obese mice; it controls a

A study conducted at the University of Wisconsin-Madison has identified a gene that could increase susceptibility to diabetes in those who carry it. Researchers discovered the gene in obese mice; it controls a