A longitudinal study conducted in Japan has shown that risk of dementia increases when glucose levels swing out of control, especially directly after meals. The study was conducted by Yutaka Kiyohara, M.D., Ph.D., and colleagues at the Kyushu University in Fukuoka, Japan. The results were reported in the September 20 issue of the journal “Neurology.”

A longitudinal study conducted in Japan has shown that risk of dementia increases when glucose levels swing out of control, especially directly after meals. The study was conducted by Yutaka Kiyohara, M.D., Ph.D., and colleagues at the Kyushu University in Fukuoka, Japan. The results were reported in the September 20 issue of the journal “Neurology.”

Individuals who had been diagnosed with diabetes were 74% more likely to develop some form of dementia over 15 years of follow-up. The study also adjusted for confounding factors. The study followed 1,017 community-dwelling older adults who did not have dementia at the beginning of the study. The participants had an oral glucose test at age 60 or older; the researchers followed them for 15 years to determine if they developed one of the various forms of dementia.

Patients with diabetes were also 2.05 times more likely to develop Alzheimer’s than individuals with normal glucose tolerance levels, after adjustment for confounding factors. As such, diabetes was specifically associated with a higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease later in life.

According to Richard Bergenstal, M.D., with the International Diabetes Center at Park Nicollet in Minneapolis, MN, the study’s results were also interesting in that they displayed a strong risk prediction of Alzheimer’s associated with post-load glucose levels during the oral glucose tolerance test.

Patients who displayed higher blood glucose levels two hours after a meal were shown to be at a higher risk of developing dementia, including Alzheimer’s.

Study participants who showed a post-meal blood glucose measurement of 7.8 to 11.0 mmol/L had a 50% greater chance of developing all-cause dementia. Those with a post-meal blood glucose measurement greater than 11.0mmol/L had 2.47-fold increase in risk of all-cause dementia and a 3.42-fold increase in risk of Alzheimer’s.

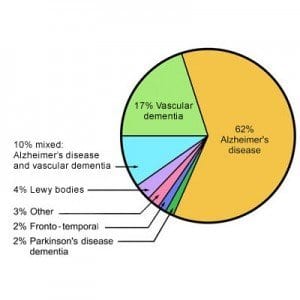

According to Kiyohara’s research group, the findings demonstrated that “that postprandial glucose regulation is critical to prevent future dementia.” Individuals with diabetes need to manage their post-meal blood glucose levels carefully since they are at a greater risk of developing dementia later in life. “Our findings emphasize the need to consider diabetes as a potential risk factor for all-cause dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, and probably vascular dementia,” added Kiyohara’s group.

Bergenstal, a previous president of the American Diabetes Association, warned that it’s as yet unclear whether improved control of post-meal insulin levels could lower the risk of dementia for patients who already have diabetes. We need to understand it a lot better before we build this into our clinical practice,” said Bergenstal. “We don’t know yet from these studies how to intervene.”

Among the participants of the study, those who displayed diabetes through an oral glucose tolerance test were 2.07 times more likely to develop vascular dementia compared to those with normal glucose tolerance. The numbers were adjusted for age and sex.

The significantly higher risk of vascular dementia in diabetes patients may be a result of the low number of cases of that type of dementia, or because diabetes is associated with hypertension and other cardiovascular complications that are linked to vascular dementia.

Hyperglycemia may have also had an effect on the development of dementia by way of atherosclerosis, oxidative stress, the accumulation of advanced protein glycation, and changes in insulin metabolism that yield altered amyloid metabolism.

Diabetes and prediabetes accounted for 14.6% of all-cause dementia, 20.1% of Alzheimer’s disease, and 17% of vascular dementia risk. The research team noted that further studies were required before the results could be generalized to other ethnic populations.