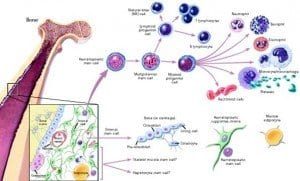

Neural stem cells may someday be used to replace the beta cells of the pancreas that are destroyed by diabetes, according to a Japanese research team. The findings, which were published in a recent issue of the journal “EMBO Molecular Medicine,” demonstrate how the shortage of transplantable, donated beta cells could be overcome by using stem cells to regenerate an individual’s own beta cells.

Neural stem cells may someday be used to replace the beta cells of the pancreas that are destroyed by diabetes, according to a Japanese research team. The findings, which were published in a recent issue of the journal “EMBO Molecular Medicine,” demonstrate how the shortage of transplantable, donated beta cells could be overcome by using stem cells to regenerate an individual’s own beta cells.

Affecting over 200 million people around the world, diabetes is caused by decreased insulin production in the pancreas—specifically, in the beta cells of the pancreas. No cure for the disease exists today, so patients must rely on supplemental insulin treatment or other therapeutics to ensure that blood glucose levels remain regulated.

The research team was headed by Dr. Tomoko Kuwabara with the AIST Institute in Tsubuka, Japan. Dr. Kuwabara’s team focused developing new ways to control stem cell differentiation in humans, which would allow scientists to transplant stem cells and give them instructions to regrow any type of cell in the human body, such as pancreatic beta cells.

Dr. Kuwabara commented that since diabetes is caused by a lack of only one type of cell, it makes a good candidate for treatment with stem cells. “As diabetes is caused by the lack of a single type of cell the condition is an ideal target for cell replacement treatments,” he said. “However donation shortages of pancreatic beta cells are a major hurdle to advancing this treatment. So a safe and easy way of using stem cells for obtaining new beta cells has been long awaited.”

Dr. Kuwabara’s team used cells from the hippocampus and olfactory bulbs—regions of the brain that scientists can easily access to obtain transplantable cells. These brain cells do not normally produce insulin in the capacity that beta cells do. However, when the neuronal cells were transplanted into diabetic rats, they began to express important characteristics normally seen in the beta cells of the pancreas. They also began to produce more insulin, resulting in a decrease of average blood glucose levels. When the transplanted cells were removed, blood glucose levels increased, revealing that the cells were responsible for the positive changes. According to the research team, this method of transplanting brain cells into the pancreas could prove to be an effective treatment for diabetes that focuses on addressing the lack of beta cells rather than medicating insulin or blood glucose levels.

“The discovery of stem cells which have virtually unlimited self-renewal raises great expectations for their use in regenerative medicine,” wrote Onur Basak and Hans Clevers, who published a close up paper in the same issue of EMBO Molecular Medicine.

“The isolation and cultivation of stem cells as a renewable source of beta cells would be a major breakthrough,” they continued.

Basak and Clevers added: “Dr Kuwabara’s team found that transplanting neural stem cells directly into the pancreas can unleash their intrinsic ability to act as critical regulators of insulin production, and most importantly they demonstrated that the cells could be gained from a patient without the need for genetic manipulation.”

“Our findings demonstrate the potential value of neural stem cells for treating diabetes without gene transfer,” said Dr. Kuwabara. “This presents an original strategy to overcome the donor shortage which has hindered cell replacement therapy.”

Physicians have known for decades that regular physical activity is one of the key methods of diabetes

Physicians have known for decades that regular physical activity is one of the key methods of diabetes  A retrospective study recently published in the journal “Arthritis Care & Research” reports that tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors could help prevent diabetes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), who commonly take TNF inhibitors to help in preventing joint disease.

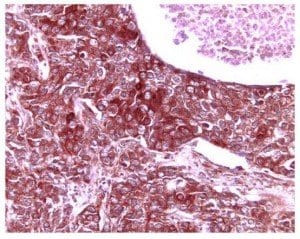

A retrospective study recently published in the journal “Arthritis Care & Research” reports that tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors could help prevent diabetes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), who commonly take TNF inhibitors to help in preventing joint disease. Researchers from the Stanford University School of Medicine have discovered that the artificial activation of an important molecular pathway could someday be used to treat various diseases. The pathway is responsible for decreases in the growth of cells that produce

Researchers from the Stanford University School of Medicine have discovered that the artificial activation of an important molecular pathway could someday be used to treat various diseases. The pathway is responsible for decreases in the growth of cells that produce

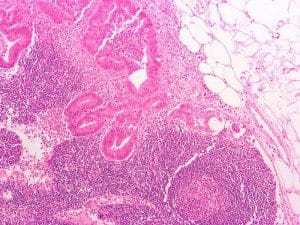

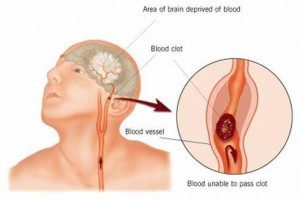

A recent population-based study conducted by researchers at Columbia University in New York found that patients who had been diagnosed with diabetes for a period of ten years or more were over three times more likely to suffer ischemic stroke. The study, called the Northern Manhattan Study, was a large, longitudinal investigation that allowed researchers to study how risk changed over long periods of time.

A recent population-based study conducted by researchers at Columbia University in New York found that patients who had been diagnosed with diabetes for a period of ten years or more were over three times more likely to suffer ischemic stroke. The study, called the Northern Manhattan Study, was a large, longitudinal investigation that allowed researchers to study how risk changed over long periods of time. For individuals with Type 1 diabetes, maintaining healthy blood sugar levels could be not only a necessity for long-term health, but also the key to staying mentally sharp. A study published in the online version of the journal “Diabetes” states that increased exposure to hyperglycemia — elevated levels of blood sugar — is associated with negative effects on brain size, including a decrease in whole brain gray matter. Meanwhile, hypoglycemia is associated with more severe decreases in occipital/parietal white matter volume.

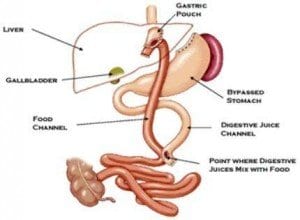

For individuals with Type 1 diabetes, maintaining healthy blood sugar levels could be not only a necessity for long-term health, but also the key to staying mentally sharp. A study published in the online version of the journal “Diabetes” states that increased exposure to hyperglycemia — elevated levels of blood sugar — is associated with negative effects on brain size, including a decrease in whole brain gray matter. Meanwhile, hypoglycemia is associated with more severe decreases in occipital/parietal white matter volume. The Utah Obesity Study has provided the first prospective, long-term controlled trial on the effects of gastric bypass surgery. The trial discovered that the cardiometabolic improvements associated with recent gastric bypass surgery also persist over long periods of time.

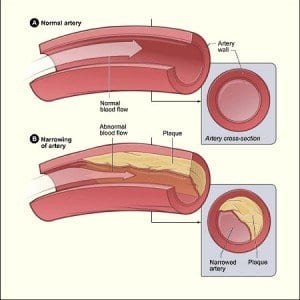

The Utah Obesity Study has provided the first prospective, long-term controlled trial on the effects of gastric bypass surgery. The trial discovered that the cardiometabolic improvements associated with recent gastric bypass surgery also persist over long periods of time. A study conducted by researchers at Kaiser Permanente shows that those with Type 2 diabetes would be wise to work at improving their cholesterol. According to the findings of the study, raising HDL cholesterol — or “good” cholesterol — could be associated with a reduction in the risk of stroke and

A study conducted by researchers at Kaiser Permanente shows that those with Type 2 diabetes would be wise to work at improving their cholesterol. According to the findings of the study, raising HDL cholesterol — or “good” cholesterol — could be associated with a reduction in the risk of stroke and